How to Actually Support Your Loved Ones

A few weeks ago someone near and dear to me landed in the hospital. As the acute situation was resolved over the next couple of weeks, she was diagnosed with a serious and potentially life-threatening medical condition.

This one hit me hard, and I wanted to do something – anything! – to make things better. So I started doing research including an inquiry with my own functional medicine doctor. When I received an email back I forwarded it to my loved one, thankful that at least I could connect her to some information that might be helpful.

Unfortunately the email I forwarded was blunt, full of assumptions, and not at all sensitive to my loved one’s situation. Pretty soon another family member called to let me know that it had hurt my loved one’s feelings. This person reminded me of the core philosophy I’ve taught to many others, one that she felt I had violated that day. I want to share it with you here so that you don’t end up hurting more than helping when one of your loved one goes through a divorce, health crisis, loss, or any of the other difficult waters that life may bring.

The Ring Theory is a concept developed by Susan Silk and Barry Goldman. Susan had an experience with cancer and was surprised at how many of her loved ones told her how scared they were, dumping their negative feelings on her when she had enough of her own fears to deal with. She and Barry developed a theory that’s helpful to caregivers and people going through any kind of crisis, giving direction on what to do (and what not to do!) by looking at where you are in relationship to the crisis. I’ve used this principle with my parents, with my kids, and with my granddaughters when they’ve gone through hard things and found it incredibly helpful.

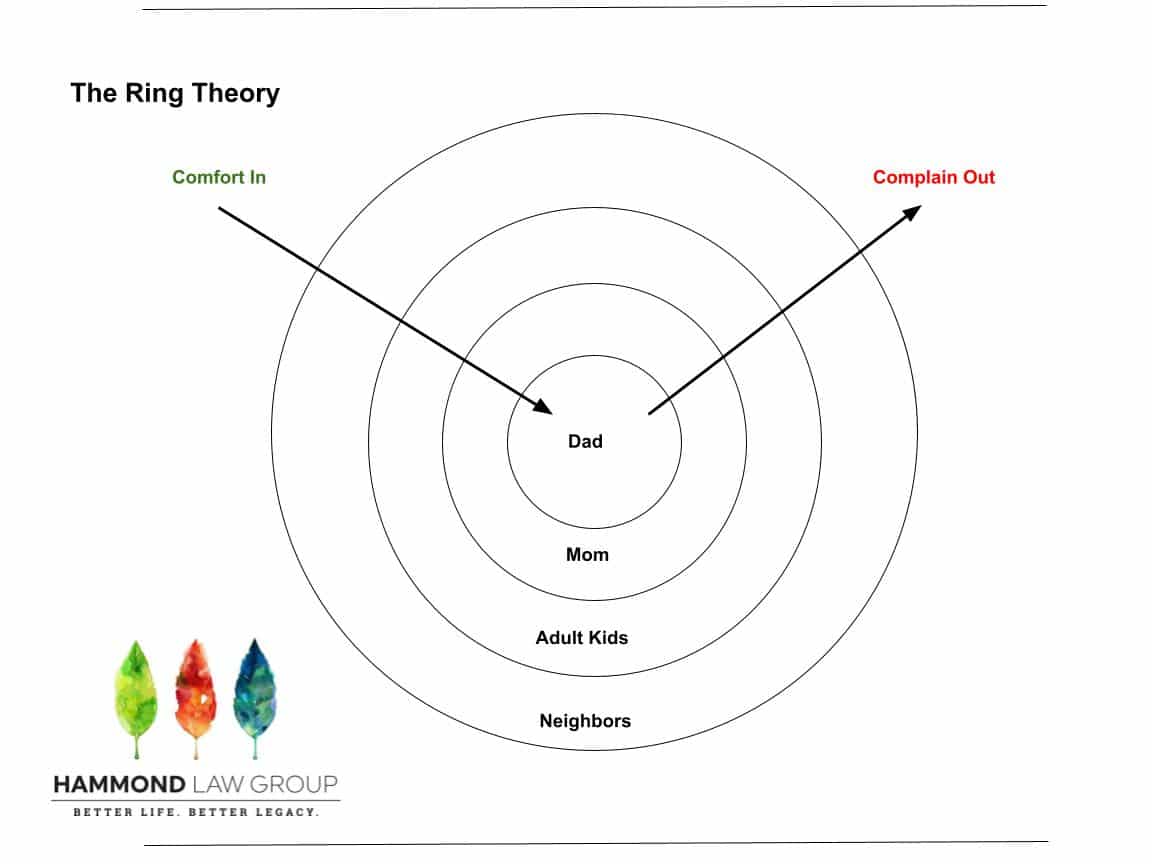

So how does it work? Start by drawing a small circle. In this circle, write the name of the person at the center of the crisis. So if Dad has dementia or cancer, his name would go in the circle.

So how does it work? Start by drawing a small circle. In this circle, write the name of the person at the center of the crisis. So if Dad has dementia or cancer, his name would go in the circle.

Now draw a slightly larger circle around the first one. In this ring, put the name of the person next closest to the crisis. So if Dad is married to Mom, you’d put Mom’s name in this circle.

Now draw another circle, in each larger circle you’ll put the names or categories of people who are next closest. So if Dad’s at the center of the ring, and Mom’s in the next circle out, maybe the adult children would be in the next ring, then close friends, then less intimate friends, then acquaintances and ‘looky loos,’ those people who really don’t have a relationship with the person in the crisis, but they have an opinion about everything.

Here’s the magic of the Ring Theory: you have a picture of who should do what when it comes to both complaining and supporting the person going through the crisis.

The person at the center of the ring can complain and moan and whine all they want, to anyone. They can say, “life isn’t fair,” “why me?!” Anything they want.

Everyone else can complain, too, but only to people in larger rings.

When you’re talking to a person in a smaller ring than yours, you should only help. That means listen, offer tangible help, encourage. The goal is only comfort and support. Not advice, people going through trauma don’t need advice.

Comfort in, dump out.

Comfort in, dump out.

Put your diagram on your refrigerator or somewhere you will remember, and share this principle with everyone else involved in your situation.

In the recent situation with my loved one, while I wasn’t complaining to her, I was giving unwanted guidance when all she wanted was love and support. Coming back to the Ring Theory and the basic principles it embodies reminded me that the only things I want to be pushing inward to her are love and support, not unsolicited information and guidance.

We all go through hard things at some point in life. Implementing the Ring Theory in your own life situations, whether you’re in crisis or in a support role, will help whoever is in crisis to truly feel loved and supported.